This week, we talk wood burning. If you enjoy reading these stories please feel free to pass this resource along to others - I’d love to have them subscribe.

Cold weather is settling in where I live in the northern US. For me, that means two things: digging out the snow shovels and lighting the woodstove to chase off the chill. Only one of these seasonal tasks leads to relaxation.

In my home, I burn some wood, mostly during the shoulder seasons in autumn and spring. This lets me defer using the natural gas boiler, which has clear and obvious climate consequences. My woodpile is stocked with local hardwood, aged, split and stacked. Some of my neighbors use pellets, a manufactured product from saw dust and some binders that looks like, well, little pellets. You buy them at your local home or hardware store or even grocery stores. But they’re basically wood.

Fireplace efficiency is more complicated than it seems

Fireplaces and stoves - either the cord wood or pellet varieties - work in chemically similar ways. Fuel + oxygen + heat creates a chain reaction that consumes more fuel, more oxygen, and produces more heat. Combustion byproducts exit your chimney and the process continues until it runs out of fuel or oxygen.

Wood or pellets are the obvious fuel, but where does that oxygen come from? The answer is that it comes from your house, where it enters your fireplace, reacts with the wood (nerd alert: technically, pyrolysis and oxidation), and then forms combustion products.

When the fuel burns away, we just add a little more wood. Air is always streaming in.

This air, now depleted of oxygen, is heated up and sent through your chimney, often at fairly high temperatures, which is an important loss of energy as the heat goes outside your home (inefficiency #1). But the air in your living room (or where ever you keep your stove) must also be replaced, and this supply comes from the outdoors, which is usually colder than indoor temperatures. This is another inefficiency. Its one of the reasons why the other rooms in your home away from your fire seem so much colder - cold air is leaking in.

Just think about that - the hotter you run your fire, the more air it consumes, which has to be replaced by more cold outdoor air which leads to more required heating.

Woodstove Efficiency Smoke and Mirrors

Fireplace vendors, and even the US EPA, like to talk about how efficient wood appliances can be - you can look it up yourself. But what these numbers really tell you is how much energy is extracted from a stick of wood to warm the stove surface, and only under very specific conditions in which the stove is operating in a test laboratory. While it accounts for the jet of wasted hot air that exits your chimney, it does not account for the equal amount of usually much colder air rushing into your home. Nor does it consider all of the variability that occurs in a stove under real world operation.

In the real world, stove dampers are turned down starving the wood of some oxygen, pellet stove thermostats start and stop combustion every so often, and we open the door and add big chunks of wood whenever they are needed. All of these changes impact stove performance, meaning you are getting less heat out of that piece of wood.

As a result, lower efficiency operation is almost guaranteed, even for stoves that fall under the most recent EPA efficiency certification1 which is a method that is being called in to question by a group of independent scientists. Their conclusion: efficiency testing has been largely shoddy, labs performing these tests have been under the improper influence of wood stove manufacturers, and EPA has not had effective compliance oversight.

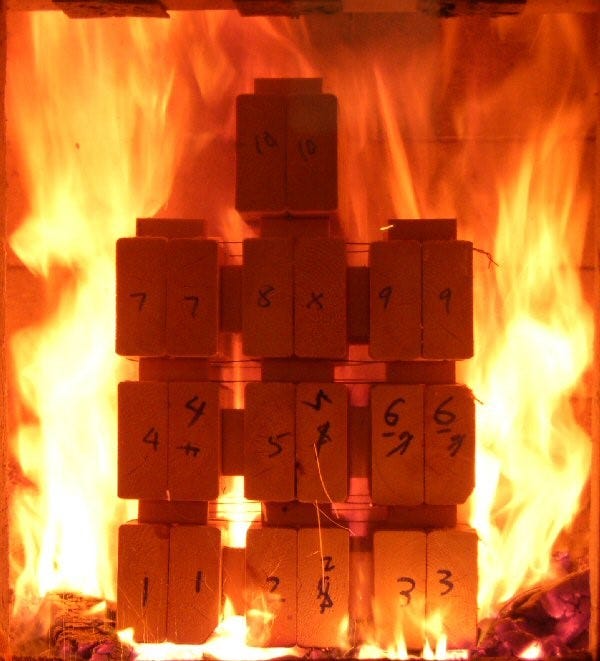

By these official (but probably flawed) test methods, my own stove is rated by the EPA at “77% overall efficiency” which sounds pretty good. But this only happens when the stove is burning full bore, the firebox is glowing bright orange, and there is a jet of hot air running up the chimney (and cold air rushes in from the outside).

The EPA testing protocol is like test fuel economy in a car based only on how it performs at high speed on the open highway, with a perfectly tuned engine and with no other passengers. Sure, many cars do very well under these conditions, but this is not how we always drive. There is stopping and starting, hauling around a bunch of heavy passengers and cargo, idling at stoplights, and so on.

The way we actually use a car determines its overall energy efficiency. The same is true for wood burning, and this is not accounted for in these efficiency reports.

“Generally, a wood-burning fireplace is a very inefficient way to heat your home.” (US EPA, https://www.epa.gov/burnwise/energy-efficiency-and-your-wood-burning-appliance)

In a review of the research, it is difficult to find objective measurements that provide real world efficiency numbers for stove operation. My hunch is that real world efficiency in the 25-35% range. But for the sake of the argument, let’s call it 60%, meaning that 40% of the potential fuel energy is wasted. Imagine how preposterous it would be if you bought ten gallons of gasoline to your car, but poured four gallons down the drain.

It’s almost impossible to calculate stove efficiency in individual cases because it depends on many different factors - chimney design, damper settings, internal stove design, or wood quality, to name a few.

But reported efficiencies are reported only under best-case scenarios, which are almost never the case.

Carbon Neutral? It Depends.

There are lots of scientific and political arguments on whether burning woody biomass is carbon neutral.

Burning a log, which releases carbon into the atmosphere, has important climate consequences. But if that carbon can be quickly captured by growing plants and trees, then it does not last very long in the atmosphere - this is carbon neutral. By that, we usually mean that for every molecule of climate changing carbon dioxide that is emitted from burning wood, there exists a natural (or sometimes man-made) process that recaptures that carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and locks it back away.

Whether or not burning of wood is carbon neutral depends on your time horizon. Where I live, the most common wood species in firewood is white or red oak. Mature trees take about 30 years to grow, which means if I were to burn oak wood, the carbon would remain in the atmosphere for about 30 years before being recaptured by a growing oak tree. On a 30 year time horizon, burning wood is indeed ‘carbon neutral’. But climate change is an imminent threat on the order of 5-10 years or less, so burning that wood in this timeframe, it is most definitely not carbon neutral.

A good rule of thumb is that a 22” tree (diameter at breast height) contains about one cord of wood. I burn a little more than one tree each year. That means I’d have to plant 30 oak trees, every year, for my wood burning to be carbon neutral.

All that being said, combustion of oil or natural gas or coal is far worse. Those fuels have carbon neutral time scales on the orders of millions of years. Carbon molecules from these fuels will effectively float around in the atmosphere, forever warming the climate. So in that context, wood burning is certainly more carbon neutral than oil and coal, but it’s almost surely not carbon neutral in the time scales we need to stop contributing to climate change.

Maybe we should come up with different terms. Is wood ‘carbon better’ than oil? Yep. Is wood carbon neutral, in terms of climate change impacts? The answer is no.

How do we stay warm then?

I take an relatively agnostic viewpoint on wood burning - I know there are distinct aesthetic pleasures to sitting in front of a warm stove, especially with family and friends. And there are real issues of fuel equity, where wood is often plentiful and inexpensive compared to other more expensive (or unavailable) heating fuels, especially in rural areas. Not everyone has many affordable alternatives, so wood will continue to be a fuel stock now and into the future.

But I definitely do not buy that this fuel is carbon neutral, nor that it is a particularly efficient use of fuel. I remain skeptical of manufacturer promises on fuel efficiencies, and have concerns that increased wood burning may lead to important health impacts for society, particularly in communities that lack fuel alternatives.

Moderate wood use can be a source of comfort for many. But there are better alternatives on the horizon. Until they arrive, I’ll use my wood stove mindfully, and with moderation.

Because I know that a warm living room is a welcome respite, especially after using those snow shovels.

Conflict of Interest Statement: I am an appointed member of the Mohawk Trails Woodland Partnership which is a group, codified in State law, to lead forest-based economic development and conservation. This group played no role in authoring this article, nor does it intentionally reflect their specific viewpoints or perspectives.

Standards of Performance for New Residential Wood Heaters, New Residential Hydronic Heaters and Forced-Air Furnaces, 80 Fed. Reg. 13672-13753 (March 16, 2015).

Nice writeup but the oaks on yew.